Deployment module Drupal là gì?

- Posted by: Bui Thi Thu Lai

- Thu, 9/01/2014, 17:21 (GMT+7)

- 0 Bình luận

Deployment module Drupal là gì?

In a Drupal development-staging-production workflow, the best practice is for new features and bug fixes to be developed locally, then moved downstream to the staging environment, and later to production.

Just how changes are pushed downstream varies, but typically the process includesFeatures, manual changes to the production user interface, drush commands, and written procedures.

Some examples include:

- A view which is part of a Feature called xyz_feature is modified; the feature is updated and pushed to the git repo; and then the feature is reverted using drush fr xyz_feature on the production site.

- A new default theme is added to the development site and tested, and pushed to the git repo; and then the new theme is selected as default on the production site'sadmin/appearance page.

- Javascript aggregation is set on the dev site'sadmin/config/development/performance page, and once everything works locally, it is set on the production via the user interface.

This approach is characterized by the following properties:

- Each incremental deployment is different and must be documented as such.

- If there exist several environments, one must keep track manually of what "remains to be done" on each environment.

- The production database is regularly cloned downstream to a staging environment, but it is impossible to tell when was the last time it was cloned.

- If an environment is out of date and does not contain any important data, it can be deleted and the staging environment can be re-cloned.

- Many features (for example javascript aggregation) are never in version control, at best only documented in an out-of-date wiki, at worst in the memory of a long-gone developer.

- New developers clone the staging database to create a local development environment.

- Automated functional testing by a continuous integration server, if done at all, uses a clone of the staging database.

The main issue I have with this approach is that it overly relies on the database to store important configuration, and the database is not under version control. There is no way to tell who did what, and when.

THE DEPLOYMENT MODULE

Using a deployment module aims to meet the following goals:

- Everything except content should be in version control: views, the default theme, settings like Javascript aggregation, etc.

- Incremental deployments should always be performed following the same procedure.

- Initial deployments (for example for a new developer or for a throwaway environment during an automated test) should be possible without cloning the database.

- Tests should be run agains a known-good starting point, not a clone of a database.

- New developers should be up and running without having to clone a database.

Essentially, anything not in version control is unreliable, and cloning the database today can yield a bug which won't be present if you clone the database tomorrow. So we'll avoid cloning the database in most cases.

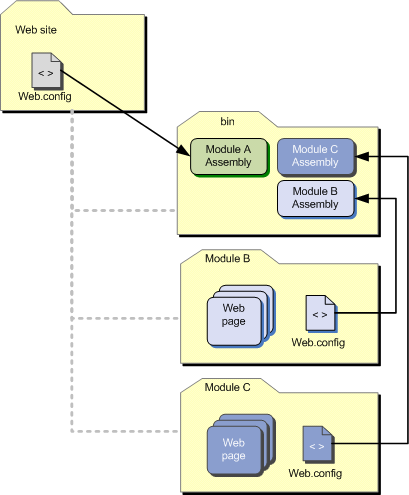

The Dcycle manifesto states that each site should have a deployment module whose job it is to keep track of deployment-related configuration. Once you have settled on a namespace for your project, for example example, by convention your deployment module should reside in sites/*/modules/custom/example_deploy.

Let's now say that we are starting a project, and our first order of business is to create a specific view: we will create the view, export it as a feature, and make the feature a dependency of our deployment module. Starting now, if all your code is under version control, all new environments (production, continuous integration, testing, new local sites) are deployed the same way, simply by creating a database and enabling the deployment module. Using Drush, you would call something like:

echo 'create database example' | mysql -uroot -proot drush si --db-url=mysql://root:root@localhost/example --account-name=root --account-pass=root drush en example_deploy -y

The first line creates the database; the second line is the equivalent of clicking though Drupal's installation procedure; and the third line activates the deployment module.

Because you have set your feature to be a dependency of your deployment module, it is activated and your view is deployed.

INCREMENTAL DEPLOYMENTS

We want the incremental deployment procedure to always be the same. Also, we don't want it to involve cloning the database, because the database is in an unknown state (it is not under version control). Another reason we don't want to clone the database is because we want to practice our incremental deployment procedure as must as possible, ideally several times a day, to catch any problems before we apply it to the production site.

My incremental deployment procedure, for all my Drupal projects, uses Drush and Registry rebuild, and goes as follows once the new code has been fetched via git:

drush rr drush vset maintenance_mode 1 drush updb -y drush cc all drush cron drush vset maintenance_mode 0

The first line (drush rr) rebuild the registry in case we moved module files since the last deployment. A typical example is moving contrib modules from sites/all/modules/ tosites/all/modules/contrib/: without rebuilding the registry, your site will be broken and all following commands will fail.

drush vset maintenance_mode 1 sets the site to maintenance mode during the update.

drush updb -y runs all update hooks for contrib modules, core, and, importantly, your deployment module (we'll get back to that in a second).

drush cc all clears all caches, which can fix some problems during deployment.

On some projects, I have found that running drush cron at this point helps avoid hard-to-diagnose problems.

Finally, move your site out of maintenance mode: drush vset maintenance_mode 0.

HOOK_UPDATE_N()S

Our goal is for all our deployments (features, bug fixes, new modules...) to be channelled though hook_update_N()s, so that the incremental deployment procedure introduced above will trigger them. Simply, hook_update_N() are functions which are called only once for each environment.

Each environment tracks the last hook_update_N() called, and when drush updb -y is called, it checks the code for new hook_update_N() and runs them if necessary. (drush updb -y is the equivalent of visiting the update.php page, but the latter method is unsupported by the Dcycle procedure, because it requires managing PHP timeouts, which we don't want to do).

hook_update_N()s is the same tried-and-true mechanism used to update database schemas for Drupal core and contrib modules, so we are not introducing anything new.

Now let's see how a few common tasks can be accomplished the Dcycle way:

EXAMPLE 1: ENABLING JAVASCRIPT AGGREGATION

Instead of fiddling with the production environment, leaving no trace of what you've done, here is an ideal workflow for enabling Javascript integration:

First, in your issue tracker, create an issue explaining why you want to enable aggregation, and take note of the issue number (for example #12345).

Next, figure out how to enable aggregation in code. In this case, a little reverse-engineering is required: on your local site, visitadmin/config/development/performance and inspect the "Aggregate JavaScript files" checkbox, noting its name property: preprocess_js. This is likely to be a variable. You can confirm that it works by calling drush vset preprocess_js 1 and reloadingadmin/config/development/performance. Call drush vset preprocess_js 0 to turn it back off again. Many configuration pages work this way, but in some cases you'll need to work a bit more in order to figure out how to affect a change programmatically, which has the neat side effect of providing you a better understanding of how Drupal works.

Now, simply add the following code to a hook_update_N() in your deployment module's .install file:

/**

* #12345: Enable javascript aggregation

*/

function example_deploy_update_7001() {

variable_set('preprocess_js', 1);

// you can also do this with Features and the Strongarm module.

}

Now, calling drush updb -y on any environment, including your local environment, should enable Javascript aggregation.

It is important to realize that hook_update_N()s are only called on environments where the deployment module is already in place, and not on new deployments. To make sure that new deployments and incremental deployments behave similarly, I call all my update hooks from my hook_install, as described in a previous post:

/**

* Implements hook_install().

*

* See http://dcycleproject.org/node/43

*/

function example_deploy_install() {

for ($i = 7001; $i < 8000; $i++) {

$candidate = 'example_deploy_update_' . $i;

if (function_exists($candidate)) {

$candidate();

}

}

}

Once you are satisfied with your work, commit it to version control:

git add sites/all/modules/custom/example_deploy/example_deploy.install git commit -am '#12345 Enabled javascript aggregation' git push origin master

Now you can deploy this functionality to any other environment using the standard incremental deployment procedure, ideally after your continuous integration server has given you the green (or in the case of Jenkins, blue) light.

EXAMPLE 2: CHANGING A VIEW

If we already have a feature which is a dependency of our deployment module, we can modify our view; update our features using the Features interface at admin/structure/features or using drush fu xyz_feature -y; then adding a newhook_update_N() to our deployment module:

/**

* #12346: Change view to remove html tags from trimmed body

*/

function example_deploy_update_7002() {

features_revert(array('xyz_feature' => array('views_view')));

}

In the above example, views_view is the machine name of the Features component affecting views. If you want to revert other components, make sure you're using the 2.x branch of Features, visit the page atadmin/structure/features/xyz_feature/recreate (where xyz_feature is the machine name of your feature), and you'll find the machine names of each component next to its human name (for example node for content types, filter for text formats, etc.).

EXAMPLE 3: CHANGING THE DEFAULT THEME

Say we create a new default theme xyz and want to enable it:

/**

* #12347: New theme for the site

*/

function example_deploy_update_7003() {

theme_enable(array('xyz'));

variable_set('theme_default', 'xyz');

}

EXAMPLE 4: ADDING AND REMOVING MODULES

I normally remove toolbar on all my sites and put admin_menu's admin_menu_toolbarinstead. To deploy the change, add admin_menu to sites/*/modules/contrib and add the following code to your deployment module:

/**

* #12348: Add a drop-down menu instead of the default menu for admins

*/

function example_deploy_update_7004() {

// make sure admin_menu has been downloaded and added to your git repo,

// or this will fail.

module_enable(array('admin_menu_toolbar'));

module_disable(array('toolbar'));

}

DON'T CHANGE PRODUCTION DIRECTLY

Of course, nothing prevents clueless users from modifying views, modules and settings on the production site directly, so I like to add hook_requirements() to perform certain checks on each environment: for example, if Javascript aggregation is turned off, you might see a red line on admin/reports/status saying "This site is designed to use Javascript aggregation, please turn it back on". You might also check that all your Features are not overridden, that the right theme is on etc. If this technique is used correctly, when a bug is reported on the production site, the admin/reports/statuspage will let you know if any settings on the production site are not what you intended, and what your automated tests expect.

NEXT STEPS: AUTOMATED TESTING AND CONTINUOUS INTEGRATION

Now that everything we do is in version control, we no longer need to clone databases, except in some very limited circumstances. We can always fire up a new environment and add dummy content for development or testing; and, provided we're using the same commit and the same operating system and version of PHP, etc., we're sure to always get the same result (which is not the case with database cloning).

Specifically, I normally add a .test file in my deployment module which enables the deployment module on a test environment, and runs tests to make sure things are working as expected.

Once that is done, it becomes easy to create a Jenkins continuous integration job to monitor the master branch, and confirm that a new environment can be created and simpletests pass.

C/C++

-

26/01/2020

-

16/06/2021

-

29/06/2021

-

30/01/2012

Database

-

18/12/2012

-

18/07/2012

-

18/07/2012

-

18/12/2012